December 2012 |

Opium Fiend: An Interview with Steven Martin

Steven Martin is the author of the fascinating new memoir Opium Fiend: A 21st Century Slave to a 19th Century Addiction. Martin, a Westerner living in southeast Asia, built one of the world's greatest collections of opium paraphernalia (antique pipes, opium lamps, etc) -- but in the process became addicted to opium himself. We recently interviewed Martin about his thoughts on collecting, opium history, and the rare books he relied upon to build his collection.

"Great collectors have great focus. They not only collect, they learn." You mention in the book that when you first began collecting opium paraphernalia, there was not a single reference book in the field. You had to learn everything from scratch. Could you talk about your self-education process?

"Great collectors have great focus. They not only collect, they learn." You mention in the book that when you first began collecting opium paraphernalia, there was not a single reference book in the field. You had to learn everything from scratch. Could you talk about your self-education process?

A recurring point throughout Opium Fiend is just how completely opium smoking in the traditional Chinese manner has been eradicated, and the lack of information in modern publications that I describe was a direct result of that. I'm not surprised nobody thought there was any value in preserving anything for posterity. After all, society wanted to destroy opium smoking, not preserve it. So the only recent information I found were a couple of articles in 1990s back issues of an Asian art magazine -- one of which turned out to be full of misinformation -- and the catalog from an exhibition of opium pipes and lamps at Stanford University Museum in 1979. That was it. There was next to nothing, but the upside to the situation was that as soon as I realized there were no real experts in the field, I took it as a challenge to become the expert.

Eventually, you found several books and articles that shed some light on opium smoking in the old days -- books like Kane's and articles like Emily Hahn's. Could you tell us how you found out about opium books/articles and other ephemera and how you hunted them down?

Eventually, you found several books and articles that shed some light on opium smoking in the old days -- books like Kane's and articles like Emily Hahn's. Could you tell us how you found out about opium books/articles and other ephemera and how you hunted them down?

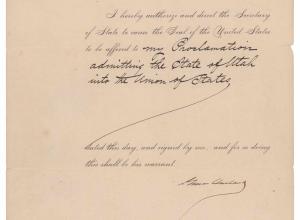

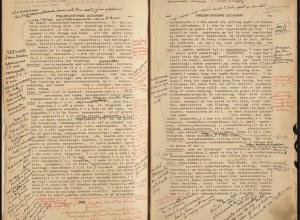

Well, as you can imagine, the Internet was a major source of information. The thing to remember though is just how much new information has been uploaded to the Internet over the last decade and how much better organized it is now compared to back then. There was a bit more wading involved when I began combing the Internet in 2001. But I eventually came up with a list of books and articles, and then I began gathering them up. H.H. Kane's 1882 book, Opium-Smoking in America and China, is a good example of how I went about collecting books and articles. An early mention I found of Kane online was a series of two articles published in the 1880s in Harper's Weekly that were more or less excerpts from his book. Then, by chance, I saw the actual book offered on eBay by a seller in Canada in 2002 or so, but I was outbid and then spent the next decade kicking myself over the loss. It took that long to find and buy another. Until then I had to content myself with a borrowed copy that I came across while doing research at the archives of Mahidol University's School of Tropical Medicine in Bangkok.

What was the most useful book on opium smoking?

Kane's book was by far the most useful. The doctor knew what he was talking about because he'd spent years doing research in the opium dens of Manhattan. He even smoked the drug to see if his own observations matched the claims of his interviewees. Most important, Kane was intent on education. He was sure that once people knew the truth about opium smoking, they would no longer risk trying it. Kane didn't stoop to Reefer Madness-style hysterics in order to demonize the drug, and thought doing so was counterproductive. So when compared to some of the other authors of the day, especially the Christian missionaries, Kane comes across as level headed and believable. Once I began experimenting with opium smoking, I wasn't too surprised to note that Kane's findings very much mirrored my own.

Emily Hahn's article for a 1969 issue of the The New Yorker is also excellent, but it's only a few thousand words. Too bad she didn't do a memoir specifically about her experiences with opium in 1930s Shanghai, because if she'd done a book-length version of her New Yorker piece, it would have been fantastic. By the way, Emily Hahn did write a memoir about her travels in Asia and other places. I urge anyone who has never heard of her to seek out a copy. Why this remarkable American adventuress is not more widely remembered is beyond me.

Were books and ephemera on opium also victims of the purges and burnings of other opium paraphernalia?

Were books and ephemera on opium also victims of the purges and burnings of other opium paraphernalia?

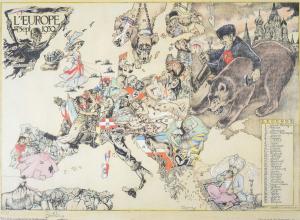

In China, yes, probably. Can you imagine how unloved a book about opium smoking would have been during the Cultural Revolution? I've heard rumors that in China there was once published an all-encompassing catalog-like publication that had illustrations of opium paraphernalia and explained the function of each piece, but if such a book ever existed, I've not been able to find it. Most everything published in the U. S. and Canada was very much against the vice, so authorities of course felt no need to destroy it. In the West, French writers were unique in that many of them seemed to want nothing more than to romanticize opium smoking. But I've never come across any reported instances of opium paraphernalia being publically destroyed in France as happened in Asia and America, and the idea that the French would bother to destroy books that showed opium smoking in a positive light seems pretty far fetched.

There are several parts in the book where you reference "collector's paranoia," that is the fear that collectors encounter when they anticipate someone else finding something first, or gaining some insight into the market, or even just strongly coveting a piece from someone else's collection. Could you talk a bit more about collectors paranoia? Do you think all collectors feel that? Do you think the feeling is heightened by collecting in an illicit arena?

There are several parts in the book where you reference "collector's paranoia," that is the fear that collectors encounter when they anticipate someone else finding something first, or gaining some insight into the market, or even just strongly coveting a piece from someone else's collection. Could you talk a bit more about collectors paranoia? Do you think all collectors feel that? Do you think the feeling is heightened by collecting in an illicit arena?

Well, obviously Opium Fiend is a memoir, not a scientific study, so I can only speak for myself and a rather small circle of collectors who I got to know. But I think for most serious collectors there is an element of competition to collecting, no matter what one collects, and any time you have people competing with one another there's potential for outrageous behavior. Some of this behavior surely falls into the "paranoia" category.

How bad can it get? It's probably apocryphal, but whenever some major and well-known work of art is stolen and then fails to turn up for decades, the theory is put forth that some mad collector has installed the piece in his basement where nobody but he can see and enjoy it. You imagine him standing there, admiring it while doing that hand-lathering gesture and laughing maniacally: "It's mine! All mine!" But like I said, it's probably apocryphal. I mean, if you couldn't show off your prize piece and inspire envy in your collecting friends, what would be the point?

I often feel that the best collections are united by an immersion, on the part of the collector, into the world of the collected material. In your case that world, of course, was smoking opium. Do you think smoking opium was necessary for building a good collection? Did it lead to an understanding of the material which you would not have otherwise had?

Smoking opium in itself wasn't as important to understanding the paraphernalia as was my having learned to prepare my own pipes. It's something like driving a car: You can be a passenger all your life but you won't really understand your vehicle until you learn to drive and get a feel for how things work. There are probably no more than a handful of people left in the world who can fluently prepare an opium pipe in the traditional Chinese manner, with all the requisite flourishes, and as a result of my "hands on" research, I can safely say that there are obscure pieces of opium-smoking paraphernalia that I alone know how to use properly. Dubious distinction perhaps, but there it is.

"Real collectors -- as opposed to mere gatherers -- become so obsessed with their collectible that they can think of nothing else." Your obsession with opium paraphernalia led you down a dangerous path of opium smoking and addiction -- yet through your obsession you built one of the greatest collections of opium paraphernalia of modern times. And in the process you've been educating the public about an area of cultural history almost completely erased and forgotten about. Some would reckon the price that you paid for this -- not the monetary price, but the emotional, physical, and mental toll of opium addiction -- to be too high. Looking back now, do you think it was worth it? Would you do it again?

"Real collectors -- as opposed to mere gatherers -- become so obsessed with their collectible that they can think of nothing else." Your obsession with opium paraphernalia led you down a dangerous path of opium smoking and addiction -- yet through your obsession you built one of the greatest collections of opium paraphernalia of modern times. And in the process you've been educating the public about an area of cultural history almost completely erased and forgotten about. Some would reckon the price that you paid for this -- not the monetary price, but the emotional, physical, and mental toll of opium addiction -- to be too high. Looking back now, do you think it was worth it? Would you do it again?

Would I do it again? If somebody invents a time machine and asks for volunteers to test it out, I'll be the first in line. I can honestly say that, despite the hardship, I'd not change a thing. That is, except for the untimely death of a dear friend.

Finally, now that you've donated your collection to the University of Idaho, have you moved on to a new arena of collecting? Or are those days past for you now?

I've had quite a few people ask that, if the donation of my collection to the University has signaled an end to my collecting opium antiques. It's true that I'm not acquiring as much as I was, but I'm still collecting when the opportunity arises. I just recently acquired a jade and enamel opium pipe that's one of the most ornate I've ever seen. I don't foresee a new collection taking the place of this one anytime in the near future. I was fortunate enough to be in the right place at the right time as far as opium antiques are concerned, and I can't imagine I'll ever be as lucky as that again with some new collectible.

[Photograph of Steven Martin and of the opium pipe with the Buddhist deity are courtesy of Mr. Martin. Photograph of Emily Hahn and of the opium den are from Wikipedia].

"Great collectors have great focus. They not only collect, they learn." You mention in the book that when you first began collecting opium paraphernalia, there was not a single reference book in the field. You had to learn everything from scratch. Could you talk about your self-education process?

"Great collectors have great focus. They not only collect, they learn." You mention in the book that when you first began collecting opium paraphernalia, there was not a single reference book in the field. You had to learn everything from scratch. Could you talk about your self-education process?A recurring point throughout Opium Fiend is just how completely opium smoking in the traditional Chinese manner has been eradicated, and the lack of information in modern publications that I describe was a direct result of that. I'm not surprised nobody thought there was any value in preserving anything for posterity. After all, society wanted to destroy opium smoking, not preserve it. So the only recent information I found were a couple of articles in 1990s back issues of an Asian art magazine -- one of which turned out to be full of misinformation -- and the catalog from an exhibition of opium pipes and lamps at Stanford University Museum in 1979. That was it. There was next to nothing, but the upside to the situation was that as soon as I realized there were no real experts in the field, I took it as a challenge to become the expert.

Eventually, you found several books and articles that shed some light on opium smoking in the old days -- books like Kane's and articles like Emily Hahn's. Could you tell us how you found out about opium books/articles and other ephemera and how you hunted them down?

Eventually, you found several books and articles that shed some light on opium smoking in the old days -- books like Kane's and articles like Emily Hahn's. Could you tell us how you found out about opium books/articles and other ephemera and how you hunted them down? Well, as you can imagine, the Internet was a major source of information. The thing to remember though is just how much new information has been uploaded to the Internet over the last decade and how much better organized it is now compared to back then. There was a bit more wading involved when I began combing the Internet in 2001. But I eventually came up with a list of books and articles, and then I began gathering them up. H.H. Kane's 1882 book, Opium-Smoking in America and China, is a good example of how I went about collecting books and articles. An early mention I found of Kane online was a series of two articles published in the 1880s in Harper's Weekly that were more or less excerpts from his book. Then, by chance, I saw the actual book offered on eBay by a seller in Canada in 2002 or so, but I was outbid and then spent the next decade kicking myself over the loss. It took that long to find and buy another. Until then I had to content myself with a borrowed copy that I came across while doing research at the archives of Mahidol University's School of Tropical Medicine in Bangkok.

What was the most useful book on opium smoking?

Kane's book was by far the most useful. The doctor knew what he was talking about because he'd spent years doing research in the opium dens of Manhattan. He even smoked the drug to see if his own observations matched the claims of his interviewees. Most important, Kane was intent on education. He was sure that once people knew the truth about opium smoking, they would no longer risk trying it. Kane didn't stoop to Reefer Madness-style hysterics in order to demonize the drug, and thought doing so was counterproductive. So when compared to some of the other authors of the day, especially the Christian missionaries, Kane comes across as level headed and believable. Once I began experimenting with opium smoking, I wasn't too surprised to note that Kane's findings very much mirrored my own.

Emily Hahn's article for a 1969 issue of the The New Yorker is also excellent, but it's only a few thousand words. Too bad she didn't do a memoir specifically about her experiences with opium in 1930s Shanghai, because if she'd done a book-length version of her New Yorker piece, it would have been fantastic. By the way, Emily Hahn did write a memoir about her travels in Asia and other places. I urge anyone who has never heard of her to seek out a copy. Why this remarkable American adventuress is not more widely remembered is beyond me.

Were books and ephemera on opium also victims of the purges and burnings of other opium paraphernalia?

Were books and ephemera on opium also victims of the purges and burnings of other opium paraphernalia?In China, yes, probably. Can you imagine how unloved a book about opium smoking would have been during the Cultural Revolution? I've heard rumors that in China there was once published an all-encompassing catalog-like publication that had illustrations of opium paraphernalia and explained the function of each piece, but if such a book ever existed, I've not been able to find it. Most everything published in the U. S. and Canada was very much against the vice, so authorities of course felt no need to destroy it. In the West, French writers were unique in that many of them seemed to want nothing more than to romanticize opium smoking. But I've never come across any reported instances of opium paraphernalia being publically destroyed in France as happened in Asia and America, and the idea that the French would bother to destroy books that showed opium smoking in a positive light seems pretty far fetched.

There are several parts in the book where you reference "collector's paranoia," that is the fear that collectors encounter when they anticipate someone else finding something first, or gaining some insight into the market, or even just strongly coveting a piece from someone else's collection. Could you talk a bit more about collectors paranoia? Do you think all collectors feel that? Do you think the feeling is heightened by collecting in an illicit arena?

There are several parts in the book where you reference "collector's paranoia," that is the fear that collectors encounter when they anticipate someone else finding something first, or gaining some insight into the market, or even just strongly coveting a piece from someone else's collection. Could you talk a bit more about collectors paranoia? Do you think all collectors feel that? Do you think the feeling is heightened by collecting in an illicit arena? Well, obviously Opium Fiend is a memoir, not a scientific study, so I can only speak for myself and a rather small circle of collectors who I got to know. But I think for most serious collectors there is an element of competition to collecting, no matter what one collects, and any time you have people competing with one another there's potential for outrageous behavior. Some of this behavior surely falls into the "paranoia" category.

How bad can it get? It's probably apocryphal, but whenever some major and well-known work of art is stolen and then fails to turn up for decades, the theory is put forth that some mad collector has installed the piece in his basement where nobody but he can see and enjoy it. You imagine him standing there, admiring it while doing that hand-lathering gesture and laughing maniacally: "It's mine! All mine!" But like I said, it's probably apocryphal. I mean, if you couldn't show off your prize piece and inspire envy in your collecting friends, what would be the point?

I often feel that the best collections are united by an immersion, on the part of the collector, into the world of the collected material. In your case that world, of course, was smoking opium. Do you think smoking opium was necessary for building a good collection? Did it lead to an understanding of the material which you would not have otherwise had?

Smoking opium in itself wasn't as important to understanding the paraphernalia as was my having learned to prepare my own pipes. It's something like driving a car: You can be a passenger all your life but you won't really understand your vehicle until you learn to drive and get a feel for how things work. There are probably no more than a handful of people left in the world who can fluently prepare an opium pipe in the traditional Chinese manner, with all the requisite flourishes, and as a result of my "hands on" research, I can safely say that there are obscure pieces of opium-smoking paraphernalia that I alone know how to use properly. Dubious distinction perhaps, but there it is.

"Real collectors -- as opposed to mere gatherers -- become so obsessed with their collectible that they can think of nothing else." Your obsession with opium paraphernalia led you down a dangerous path of opium smoking and addiction -- yet through your obsession you built one of the greatest collections of opium paraphernalia of modern times. And in the process you've been educating the public about an area of cultural history almost completely erased and forgotten about. Some would reckon the price that you paid for this -- not the monetary price, but the emotional, physical, and mental toll of opium addiction -- to be too high. Looking back now, do you think it was worth it? Would you do it again?

"Real collectors -- as opposed to mere gatherers -- become so obsessed with their collectible that they can think of nothing else." Your obsession with opium paraphernalia led you down a dangerous path of opium smoking and addiction -- yet through your obsession you built one of the greatest collections of opium paraphernalia of modern times. And in the process you've been educating the public about an area of cultural history almost completely erased and forgotten about. Some would reckon the price that you paid for this -- not the monetary price, but the emotional, physical, and mental toll of opium addiction -- to be too high. Looking back now, do you think it was worth it? Would you do it again?Would I do it again? If somebody invents a time machine and asks for volunteers to test it out, I'll be the first in line. I can honestly say that, despite the hardship, I'd not change a thing. That is, except for the untimely death of a dear friend.

Finally, now that you've donated your collection to the University of Idaho, have you moved on to a new arena of collecting? Or are those days past for you now?

I've had quite a few people ask that, if the donation of my collection to the University has signaled an end to my collecting opium antiques. It's true that I'm not acquiring as much as I was, but I'm still collecting when the opportunity arises. I just recently acquired a jade and enamel opium pipe that's one of the most ornate I've ever seen. I don't foresee a new collection taking the place of this one anytime in the near future. I was fortunate enough to be in the right place at the right time as far as opium antiques are concerned, and I can't imagine I'll ever be as lucky as that again with some new collectible.

[Photograph of Steven Martin and of the opium pipe with the Buddhist deity are courtesy of Mr. Martin. Photograph of Emily Hahn and of the opium den are from Wikipedia].