Guest Blog: The Woman Reader

The Woman Reader

Reviewed by Edith Vandervoort

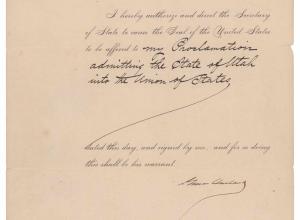

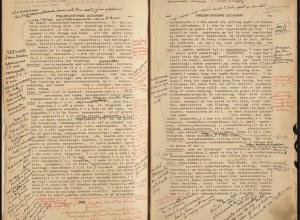

One could confidently say that all women in Western societies are permitted to enjoy the pleasures of reading. We are able to chose what we would like to read and how often we want to read. This is, even today, not the case in countries with restrictive rights for women, nor was this the case throughout much of history. In her engaging book, The Woman Reader (Yale UP, 2012), Belinda Jack traces the history of reading and education for women--notably linked to the accomplishments of the women's movement--and, with the inclusion of drawing and photographs, highlights important female readers, writers, and literary critics.

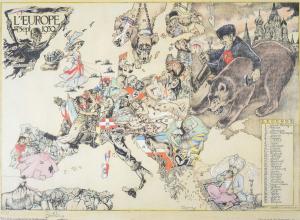

Reading for women (and men) was based on whether or not one was wealthy and had the books and the time to read. In the twelfth century, book ownership was limited to members of the nobility, but convents, which had been established as early as the fifth century when they served to offer protection from the scourges of war, provided a more egalitarian system of education in French, English, and Latin for women of various socioeconomic classes. They varied greatly by the number of book bequests and the literacy of the community, but provided women with the opportunity to achieve a high level of scholarship. In the early middle ages, men and women collaborated in writing the scripture for the purpose of serving God in the conversion of non believers. With the invention of the printing press in the sixteenth century, women largely read religious works, but also secular materials on "acceptable" topics. Romances were not included in this category and were, for many centuries, considered morally damaging and conducive to frivolity and the release of inhibited sexual desires. The Reformation provoked contentious, often dangerous religious ideas. At this time, women began to write to express their religious and political views. With improved technology came the increased availability of secular reading materials and, with it, the degradation of women through inexpensively produced pamphlets and booklets, leading to hotly-debated rebuttals written by women.

Reading for women (and men) was based on whether or not one was wealthy and had the books and the time to read. In the twelfth century, book ownership was limited to members of the nobility, but convents, which had been established as early as the fifth century when they served to offer protection from the scourges of war, provided a more egalitarian system of education in French, English, and Latin for women of various socioeconomic classes. They varied greatly by the number of book bequests and the literacy of the community, but provided women with the opportunity to achieve a high level of scholarship. In the early middle ages, men and women collaborated in writing the scripture for the purpose of serving God in the conversion of non believers. With the invention of the printing press in the sixteenth century, women largely read religious works, but also secular materials on "acceptable" topics. Romances were not included in this category and were, for many centuries, considered morally damaging and conducive to frivolity and the release of inhibited sexual desires. The Reformation provoked contentious, often dangerous religious ideas. At this time, women began to write to express their religious and political views. With improved technology came the increased availability of secular reading materials and, with it, the degradation of women through inexpensively produced pamphlets and booklets, leading to hotly-debated rebuttals written by women.

The commercialization of books thrived and women were encouraged to read advice manuals, how-to books on household activities, books on etiquette, but also pulp fiction. The debate of whether or not women should be educated abated and women became more assertive. Various salons in the seventeenth century and the Bluestockings in the eighteenth century were intellectual societies where women could freely exchange ideas. Rousseau's theories proclaiming that women should be educated to promote men's happiness was discarded and in the eighteenth century women's magazines, printed for the sole purpose of pleasure in reading what other women wrote, increased in number. The idea of reading for personal edification eventually became largely accepted for all people.

Jack's well-researched and fascinating book makes us appreciate the gift of reading and equally conscientious of how slaves, women, and disenfranchised populations are manipulated through illiteracy and the lack of quality education.

--Edith Vandervoort is a freelance writer based in California.

Reviewed by Edith Vandervoort

One could confidently say that all women in Western societies are permitted to enjoy the pleasures of reading. We are able to chose what we would like to read and how often we want to read. This is, even today, not the case in countries with restrictive rights for women, nor was this the case throughout much of history. In her engaging book, The Woman Reader (Yale UP, 2012), Belinda Jack traces the history of reading and education for women--notably linked to the accomplishments of the women's movement--and, with the inclusion of drawing and photographs, highlights important female readers, writers, and literary critics.

Reading for women (and men) was based on whether or not one was wealthy and had the books and the time to read. In the twelfth century, book ownership was limited to members of the nobility, but convents, which had been established as early as the fifth century when they served to offer protection from the scourges of war, provided a more egalitarian system of education in French, English, and Latin for women of various socioeconomic classes. They varied greatly by the number of book bequests and the literacy of the community, but provided women with the opportunity to achieve a high level of scholarship. In the early middle ages, men and women collaborated in writing the scripture for the purpose of serving God in the conversion of non believers. With the invention of the printing press in the sixteenth century, women largely read religious works, but also secular materials on "acceptable" topics. Romances were not included in this category and were, for many centuries, considered morally damaging and conducive to frivolity and the release of inhibited sexual desires. The Reformation provoked contentious, often dangerous religious ideas. At this time, women began to write to express their religious and political views. With improved technology came the increased availability of secular reading materials and, with it, the degradation of women through inexpensively produced pamphlets and booklets, leading to hotly-debated rebuttals written by women.

Reading for women (and men) was based on whether or not one was wealthy and had the books and the time to read. In the twelfth century, book ownership was limited to members of the nobility, but convents, which had been established as early as the fifth century when they served to offer protection from the scourges of war, provided a more egalitarian system of education in French, English, and Latin for women of various socioeconomic classes. They varied greatly by the number of book bequests and the literacy of the community, but provided women with the opportunity to achieve a high level of scholarship. In the early middle ages, men and women collaborated in writing the scripture for the purpose of serving God in the conversion of non believers. With the invention of the printing press in the sixteenth century, women largely read religious works, but also secular materials on "acceptable" topics. Romances were not included in this category and were, for many centuries, considered morally damaging and conducive to frivolity and the release of inhibited sexual desires. The Reformation provoked contentious, often dangerous religious ideas. At this time, women began to write to express their religious and political views. With improved technology came the increased availability of secular reading materials and, with it, the degradation of women through inexpensively produced pamphlets and booklets, leading to hotly-debated rebuttals written by women. The commercialization of books thrived and women were encouraged to read advice manuals, how-to books on household activities, books on etiquette, but also pulp fiction. The debate of whether or not women should be educated abated and women became more assertive. Various salons in the seventeenth century and the Bluestockings in the eighteenth century were intellectual societies where women could freely exchange ideas. Rousseau's theories proclaiming that women should be educated to promote men's happiness was discarded and in the eighteenth century women's magazines, printed for the sole purpose of pleasure in reading what other women wrote, increased in number. The idea of reading for personal edification eventually became largely accepted for all people.

Jack's well-researched and fascinating book makes us appreciate the gift of reading and equally conscientious of how slaves, women, and disenfranchised populations are manipulated through illiteracy and the lack of quality education.

--Edith Vandervoort is a freelance writer based in California.