Forgery, Fiction, and Poe with Author Bradford Morrow

In our current issue, Nicholas Basbanes profiles author and book collector Bradford Morrow, whose new novel, The Forger’s Daughter, a sequel to his 2014 novel, The Forgers, hit bookstores this week.

To mark the occasion, we’re publishing this Q&A with Morrow about his writing process and the literary treasures at the heart of his narrative, courtesy of his publisher.

We were first introduced to Will in The Forgers. What made you decide to continue his story?

In a word, curiosity. Curiosity fueled by a deep, lingering attachment I felt toward even the most reprehensible of characters in The Forgers. I needed to find out what happened to Will and the others after that final bittersweet Christmastime scene at the end of the novel, which was charged with heartfelt hopes but also unresolved, perilous secrets.

Will and his nemesis, Henry Slader, had reached a violent climax in their rivalry as master forgers, with Will maimed for life and Slader sentenced to prison. Will and his wife Meghan fled rural Ireland, which was supposed to have been their sanctuary but proved very much otherwise, and returned to New York to start their lives over. They have a precocious little girl, Nicole, whose uncanny skills as a calligrapher and artist left me wondering if she might one day be forced to grapple with some of the same decisions her father had faced.

While I didn’t originally write The Forgers with a sequel in mind, once it was published and out there in the world, I was surprised by how many readers asked me when I was going to write a continuation of the story. So when it became clear that Will wasn’t done with me, and I wasn’t done with him either—not to mention Meghan, Slader, Atticus, Nicole, and others—I started filling my notebook with sketches, ideas, and possible timelines for The Forger’s Daughter.

Could you talk a little about your decision to have more than a single narrator in The Forger’s Daughter?

By the end of The Forgers, Will had revealed himself to be, shall we say, something of an unreliable narrator. While I was quite comfortable with his voice and did consider letting him continue his narrative twenty years later, I also felt it would be complicating and compelling for his wife, Meghan, to counterpoint with her own independent version of events. Like most couples, they know each other very well, and yet there are hidden truths that remain unshared with one another, chasms of misapprehension that the astute reader can fathom even as husband and wife cannot. Once I settled into the two voices and dual (sometimes dueling) perspectives it became very natural, even necessary, to write the book this way. Since forgery has a lot to do with perceptions and divergent realities, it seemed to me a perfect way for the novel to be voiced.

Both your narrator and villain are forgers, and Will’s daughter is in danger of becoming one herself. What makes forgery so compelling to you as a craft and crime?

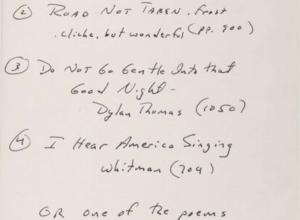

First of all, for a literary forger to be a world-class master, he or she needs to possess an expertise in a wide range of disciplines. Being a first-rate calligrapher is just one of the required skills. You must be knowledgeable about period papers and inks, about chemistry, history, biography, linguistics, and have a profound empathy for and understanding of the writer you propose to forge. What’s more, you must know your marketplace, its intricacies and endless vicissitudes—Faulkner, for instance, has leveled off in recent years, so perhaps an Austen missive, previously undiscovered, might be a better, if chancier, gambit.

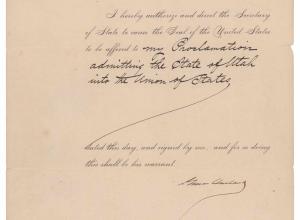

So there’s this scholarly side of the forger’s art that intrigues me. But I’m also fascinated by the high-wire chutzpah it takes to convincingly forge a document by, say, Edgar Allan Poe. Illegalities and ethics aside, to pull off such a stunt requires a cool-headed brazenness, an anti-authoritarian moxie coupled with a screw-you attitude toward the establishment’s experts, the gatekeepers any forger worth his or her salt inherently detests and wants to one-up. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not condoning this line of work! Just that it’s such a rare bird, perhaps one or two in a generation, who can combine the eclectic skills necessary to be a major forger.

I’m also interested in the term “forger” itself. What a knotty word it is. It can stand for positive things—forging ahead against the odds, forging tools in a furnace. In the fourteenth century it meant to make, to create and shape, not to counterfeit or falsify. The complexity of the word and of the various acts it signifies remains compelling to me even after having written two novels with forgery at their center. Fiction, too, is a kind of forgery, isn’t it? Writing words and inventing characters that could be deemed unreal but for the fact that they come alive in readers’ imaginations. Poe was certainly aware of the fine line between reality and fantasy, fact and fiction, madness and sanity. These most gray of areas intrigue me, too.

Tell us about the literary treasure at the heart of The Forger’s Daughter, the first edition of Edgar Allan Poe’s Tamerlane.

Just as The Forgers was steeped in Arthur Conan Doyle, The Forger’s Daughter is immersed in Edgar Allan Poe, and, in particular, his legendarily rare first book, published anonymously in 1827, when he was just eighteen-years-old. Known as the Black Tulip of American literature, Tamerlane was issued in only a handful of copies by an obscure Boston printer named Calvin F.S. Thomas. To Poe’s chagrin, it basically disappeared upon arrival, without so much as a single review. The Boston Lyceum included a note possibly about Tamerlane, by a critic named Samuel Kettell, who wrote of “a young gentleman who lately made his debut as an author by publishing a small vol. of misc. Poems, which the critics have read without praising, and the ladies have praised without reading.” An inauspicious beginning, to say the least.

As a lifelong bibliophile, I was excited to do some deep research into this Holy Grail of books, of which only a dozen examples are known to have survived. Early on in the project, I was fortunate to be introduced to the greatest Poe collector in the world, Susan Jaffe Tane, who owns the most iconic Tamerlane out there. Distinguished by the stain on its front cover, possibly courtesy of some nineteenth-century whiskey drinker who used it as a coaster, Susan’s copy was one of three here in New York that I was able to examine closely. I was nervous at first about handling a fragile treasure worth well north of a million dollars but also reveling in the moment.

There is so much about Poe’s life and work in your book. What kind of research did you do to include so many rich details?

Researching this book was pure joy. I was privileged to carry on extensive correspondences with several of our foremost Poe scholars. Chris Semtner, curator of the Edgar Allan Poe Museum in Richmond, Virginia, answered a wide array of my insanely detailed queries, as did the renowned Poe expert Richard Kopley, who is currently at work on a definitive biography. At the end of the day, they became my friends, curious to see how I was going to blend fiction with fact as a thirteenth copy of Tamerlane surfaced in my novel. Librarians, rare book dealers, auction gallery veterans—I sought advice and help from all corners of the literary world. Carolyn Vega, director of the Berg Collection at the New York Public Library, was kind enough to allow me into her sanctum sanctorum, where I—suppressing my giddiness, marveling at my good fortune—examined their two copies of Tamerlane, as well as priceless original handwritten Poe manuscripts and letters. All my research was as extensive and hands-on as possible.

If I admired Edgar Allan Poe before I started work on The Forger’s Daughter, by the end of writing the book, my love for the man—blazingly brilliant, tortured, capricious, enigmatic, willful, dark, romantic, visionary—had exponentially grown. I keep some framed vintage photographs of writers who inspire me—Beckett, Hardy, Virginia Woolf in her reading chair at Monk’s House, and recently added a portrait of Poe to the group, an 1876 albumen print copy of the famous “Stella” daguerreotype taken four months before his death in 1849. While Woolf and Hardy gaze toward the distance, Beckett and Poe stare me right in the eye.

You also have a wealth of knowledge about literary rarities. What is your background in rare books? How did you start collecting?

When I left home to attend college, I haunted a bookshop in downtown Boulder, near the campus of the University of Colorado, and began buying so many early printed books and first editions that I wound up working at the place to pay my bills. Collecting became my addiction—“a gentle madness,” as the great bookman, Nicholas Basbanes, calls it. Even though I was a serious fusion jazz musician and quasi-hippie, I was also friends, though barely out of my teens, with the distinguished librarian of the rare books room in Olin Library. I became addicted to buying seventeenth- and eighteenth-century books, using them as time capsules to get closer to their authors—Fielding’s Miscellanies, Smollett’s Roderick Random, Sir Thomas Browne’s Pseudodoxia Epidemica—and studied leather bookbinding and restoration.

When I went to graduate school at Yale on a Danforth Fellowship, I found myself moonlighting as a waiter so I could buy first editions of Tom Jones and Tristram Shandy from a local rare books firm in New Haven. From there I ended up in Santa Barbara, California, working at another rare books shop before going out on a financial limb, having borrowed some money from a relative at a usurious interest rate, to open my own business. By my mid- to late twenties I’d become a full-fledged bibliomaniac, handling everything from F. Scott Fitzgerald and John Steinbeck manuscripts to incunabula (books printed before 1500) and Jack Kerouac rarities (one of the books in my collection now is Kerouac’s own copy of his first book, The Town and the City).

Though I sold my business to start the literary journal, Conjunctions, when I was thirty, I never stopped acquiring, and even privately dealing in, rare books. My collection is simply a part of my being, odd as that may sound. Reading, writing, editing, teaching, collecting books is second nature to me. Without them, I imagine I’d feel diminished, maybe even bereft. Eccentric as it might sound to others, I consider myself lucky that books have been constant companions to me over the course of a sometimes labyrinthine life.