Picturing the Unpictureable

When you publish a book with a university press, the likelihood, far more often that not, is that you will generate a modicum of attention in your field of enquiry, and if you are lucky, earn the recognition you so richly deserve among your peers. Very rarely--though there certainly are a number of remarkable exceptions--do you get the kind of traction in the mainstream media that will attract the attention you need to spark a flurry of sales and assure continued commentary.

I know a little bit about this phenomenon, having recently written a centennial history of Yale University Press (A World of Letters was published just a year ago next month), and taken the opportunity that project gave me to look into the overall practice of academic publishing itself. What in the world of trade publishing we would call bestsellers, though infrequent, are by no means unknown among university press books.

A few examples are instructive: John Kennedy Toole's Confederacy of Dunces with Louisiana State University Press (1980); T. H. Whyte's Book of Merlyn with the University of Texas Press (1977); The I Ching or Book of Changes with Princeton University Press (1967); Carlos Castenada's Teachings of Don Juan with the University of Califorina Press (1968); Eudroa Welty's One Writer's Beginnings with Harvard University Press (1984); Eugene O'Neill's Long Day's Journey Into Night (1956) and David Riesman's The Lonely Crowd (1950), both with Yale, and both with total sales over the past half-century of 1.5 million each, and perhaps the most unlikely of all, Tom Clancy's thriller, The Hunt for Red October, with the Naval Institute Press (1984). Like Clancy's book, which became a major motion picture, a few other university press books have made their way to the silver screen, most notably Norman Maclean's autobiographical novella with the University of Chicago Press, A River Runs Through It (1976), and Al Rose's Storyville, New Orleans with the University of Alabama Press (1974), which was adapted into Louis Malle's 1978 film, Pretty Baby, starring Brook Shields.

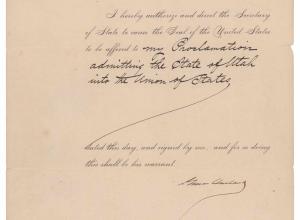

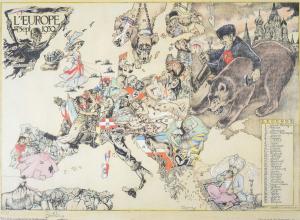

I offer all of this discursive background as prelude to my take on a news story that has been making the rounds over the past couple of weeks involving Yale University Press--which, as I stated above, I have recently written about, so regard this, please, as a disclosure of sorts--involving a book scheduled for publication this fall, The Cartoons That Shook the World by Jytte Klausen, a professor of comparative politics at Brandeis University, and the decision by the press to remove all the illustrations that were to be included, most pointedly those dealing with the Prophet Mohammed. This move was made necessary by Klausen's examination of the international incident that followed publication of a dozen cartoons in the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten in September 2005, which featured some derisive caricatures of Mohammed. The excision was made, according to Yale Press director John Donatich, after consultation with numerous national security experts, who felt that republication of the images could lead to a new wave of violence.

Press coverage for a new book is always welcome, of course, but certainly not the kind of attention that has attended this decision. The response has been mixed, though a good deal of it has accused Yale of caving in to outside pressure and throttling academic expression. The headline for a piece Christopher Hitchens wrote for Slate, "Yale Surrenders," pretty much summarizes his position. Hitchens' piece is available at the above link, so I don't need to summarize it here, beyond pointing out that he did, in the piece, what any curious individual can also do, which is to find all the offending caricatures online. He even gives a link for those interested in seeing the illustrations, though I note that Slate does not reproduce any of them either. (I wonder why that might be?)

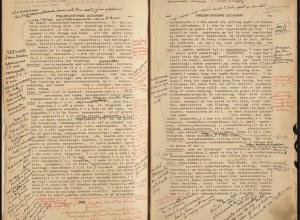

Donatich is adamant that none of Klausen's text has been removed or edited, so her findings as a social scientist have not in any way been toned down or altered. What she has written, in other words, and what was vetted, argued and defended through peer review for publication, is being published as is. While it does seem a bit odd that a book about illustrations should now contain no illustrations, I nevertheless have to say I sympathize, most reluctantly, with Donatich in his decision. It is an extraordinarily special circumstance, not one that is likely to be repeated any time soon. These are crazy times, and since you are removing something that is not new to your pages in the first instance--these would be reprints of earlier published images, after all, and are readily available to anyone who wishes to find them online--and if this material has the potential to incite a truly nasty situation, then you have a responsibility to pause and do, I think, what you have to do.

Going back to the lead of this entry, which deals with university press books and bestsellers, it is worth noting that Yale has moved the publication date of The Cartoons that Shook the World up from November to September. Donatich told The Chronicle of Higher Education (a link, unfortunately, is not available to non-subscribers), that the Press is "supporting the book completely and boldly" and "crashing the production schedule to take advantage of the media." I, for one, will be most interested now in reading the book, as I am sure many thousands of others who otherwise would have known nothing about it will as well.

As a relevant sidelight, especially one in a gently mad blog, it is worth noting that signed copies of Kurt Westergaard's drawings of Mohanned, according to the Copenhagen Post, are now collector's items, with 870 copies of a 1,000-copy limited edition already sold as of two weeks ago--at $250 a pop.

I know a little bit about this phenomenon, having recently written a centennial history of Yale University Press (A World of Letters was published just a year ago next month), and taken the opportunity that project gave me to look into the overall practice of academic publishing itself. What in the world of trade publishing we would call bestsellers, though infrequent, are by no means unknown among university press books.

A few examples are instructive: John Kennedy Toole's Confederacy of Dunces with Louisiana State University Press (1980); T. H. Whyte's Book of Merlyn with the University of Texas Press (1977); The I Ching or Book of Changes with Princeton University Press (1967); Carlos Castenada's Teachings of Don Juan with the University of Califorina Press (1968); Eudroa Welty's One Writer's Beginnings with Harvard University Press (1984); Eugene O'Neill's Long Day's Journey Into Night (1956) and David Riesman's The Lonely Crowd (1950), both with Yale, and both with total sales over the past half-century of 1.5 million each, and perhaps the most unlikely of all, Tom Clancy's thriller, The Hunt for Red October, with the Naval Institute Press (1984). Like Clancy's book, which became a major motion picture, a few other university press books have made their way to the silver screen, most notably Norman Maclean's autobiographical novella with the University of Chicago Press, A River Runs Through It (1976), and Al Rose's Storyville, New Orleans with the University of Alabama Press (1974), which was adapted into Louis Malle's 1978 film, Pretty Baby, starring Brook Shields.

I offer all of this discursive background as prelude to my take on a news story that has been making the rounds over the past couple of weeks involving Yale University Press--which, as I stated above, I have recently written about, so regard this, please, as a disclosure of sorts--involving a book scheduled for publication this fall, The Cartoons That Shook the World by Jytte Klausen, a professor of comparative politics at Brandeis University, and the decision by the press to remove all the illustrations that were to be included, most pointedly those dealing with the Prophet Mohammed. This move was made necessary by Klausen's examination of the international incident that followed publication of a dozen cartoons in the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten in September 2005, which featured some derisive caricatures of Mohammed. The excision was made, according to Yale Press director John Donatich, after consultation with numerous national security experts, who felt that republication of the images could lead to a new wave of violence.

Press coverage for a new book is always welcome, of course, but certainly not the kind of attention that has attended this decision. The response has been mixed, though a good deal of it has accused Yale of caving in to outside pressure and throttling academic expression. The headline for a piece Christopher Hitchens wrote for Slate, "Yale Surrenders," pretty much summarizes his position. Hitchens' piece is available at the above link, so I don't need to summarize it here, beyond pointing out that he did, in the piece, what any curious individual can also do, which is to find all the offending caricatures online. He even gives a link for those interested in seeing the illustrations, though I note that Slate does not reproduce any of them either. (I wonder why that might be?)

Donatich is adamant that none of Klausen's text has been removed or edited, so her findings as a social scientist have not in any way been toned down or altered. What she has written, in other words, and what was vetted, argued and defended through peer review for publication, is being published as is. While it does seem a bit odd that a book about illustrations should now contain no illustrations, I nevertheless have to say I sympathize, most reluctantly, with Donatich in his decision. It is an extraordinarily special circumstance, not one that is likely to be repeated any time soon. These are crazy times, and since you are removing something that is not new to your pages in the first instance--these would be reprints of earlier published images, after all, and are readily available to anyone who wishes to find them online--and if this material has the potential to incite a truly nasty situation, then you have a responsibility to pause and do, I think, what you have to do.

Going back to the lead of this entry, which deals with university press books and bestsellers, it is worth noting that Yale has moved the publication date of The Cartoons that Shook the World up from November to September. Donatich told The Chronicle of Higher Education (a link, unfortunately, is not available to non-subscribers), that the Press is "supporting the book completely and boldly" and "crashing the production schedule to take advantage of the media." I, for one, will be most interested now in reading the book, as I am sure many thousands of others who otherwise would have known nothing about it will as well.

As a relevant sidelight, especially one in a gently mad blog, it is worth noting that signed copies of Kurt Westergaard's drawings of Mohanned, according to the Copenhagen Post, are now collector's items, with 870 copies of a 1,000-copy limited edition already sold as of two weeks ago--at $250 a pop.